In the aftermath of the debt-ceiling debate, investors are preparing for an influx of more than $1 trillion in Treasury bills, which could trigger a new bout of volatility in financial markets.

Some on Wall Street are concerned that the approximately $850 billion in bond issuance that was postponed until a debt-ceiling agreement was reached — sales are expected between now and the end of September, according to JPMorgan analysts — will overwhelm buyers, jolting markets and increasing short-term borrowing costs.

Many are concerned about the possibility of unanticipated problems in the financial infrastructure, where daily transactions worth trillions of dollars could cause market-wide disruptions. Money-market interest rates skyrocketed in 2019 during a period of low liquidity, necessitating Federal Reserve intervention.

Jon Maier, chief investment officer of Global X, a provider of exchange-traded funds, stated, “When you dump a large amount of debt into the market, it causes dislocation.” “Investors are underestimating that.”

Recent months have witnessed relatively calm market conditions. The S&P 500 has gained 12% so far this year, supported by a robust labour market, the AI-led tech stock rally, and indications that the Federal Reserve is nearing the end of its interest-rate campaign. The Cboe Volatility Index, also known as Wall Street’s fear gauge because it monitors the cost of options that investors frequently purchase to hedge against stock declines, is currently hovering near multiyear lows.

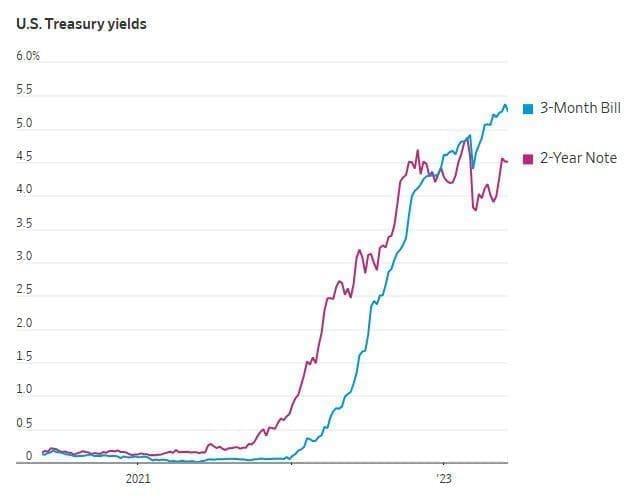

The calm comes despite the fact that short-term bond yields have already risen in recent weeks, buoyed by expectations that the Fed will maintain higher rates for an extended period of time. Tuesday’s two-year yield closed at 4.523%, up roughly 0.8 percentage point from its yearly lows a month ago. The 10-year yield ended at 3.69 percent.

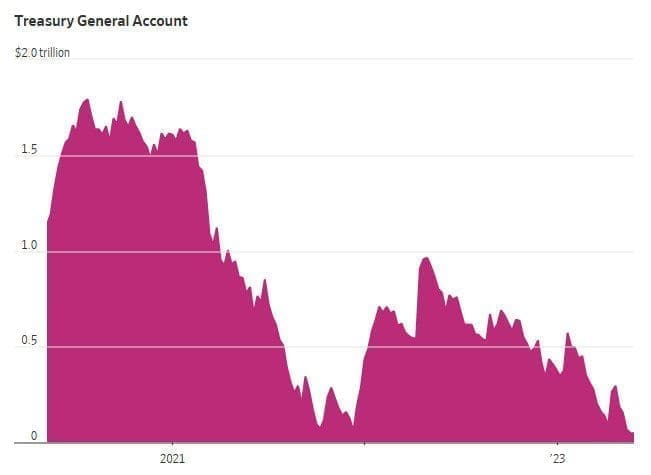

Currently, the Treasury Department is quickly restocking its treasuries. As of the end of May, a weaker-than-anticipated tax season and “extraordinary measures” enacted during the debt-ceiling fight to continue paying the government’s expenses have drained its checking account held at the Fed to below $50 billion. Officials previously projected a $600 billion balance for what is known as the Treasury General Account, or TGA.

As a result, the so-called primary dealers could be effectively compelled to finance the replenishment of the TGA, which could have a negative impact on the large institutions that are required by government contract to bid at Treasury auctions. Simultaneously, regulators are attempting to increase banks’ capital buffers to prevent another banking crisis. The Fed is allowing its balance sheet to decline, thereby further depleting market liquidity.

However, historical evidence suggests that even if banks withdrew from short-term funding markets, Fed officials would swiftly put out any fires. In September 2019, the central bank introduced a facility to provide banks with cash, despite the unclear cause of the rate rise. This facility, which lowered rates almost immediately, now exists as a permanent safeguard to assist the Fed in keeping rates under control.

Joseph Brusuelas, principal and chief economist at RSM US, stated, “It is this unintended, unexamined event that causes a clogging of the financial plumbing.” “This does not mean that the pessimists are correct; if a hiccup occurs, the Fed will intervene.”

The latest programme for at-risk banks, created during the regional banking crisis in March, reaffirmed the Fed’s willingness to aid the banking system, according to some analysts.

According to strategists, the best-case scenario is if money-market funds serve as the primary financiers for this round of bond issuance. Such funds, which invest a significant portion of their more than $5 trillion in short-term safe assets, could consume a substantial portion of the supply by withdrawing the $2.1 trillion they have deposited at the Fed’s overnight reverse repurchase facility, also known as a reverse repo. This would presumably lessen the impact on broader markets.

To accomplish this, the government must offer higher yields on T-bills in order to entice investors away from the Fed’s highly secure daily facility. In April 2020, when the Treasury issued more than $1.3 trillion of these bonds, the rates on 3-month bills rose 0.20 percentage points above the benchmark secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) for overnight lending.

According to analysts at Deutsche Bank, bill yields could expand by 0.10 to 0.15 basis points above SOFR this time but are unlikely to increase further. According to analysts, the fact that this issuance occurs at a moment when markets lack central bank support may complicate the comparison.

Given that the Fed offers a reverse repo rate facility of 5.05%, which would increase if it increased the fed-funds target range, the U.S. government could be forced to borrow more than $1 trillion at rates close to 6%. According to data from the Treasury Department, the United States could borrow on the same market for 0.1% a year and a half ago.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen cautioned Congress that the government’s increased funding costs were cause for concern due to the ambiguity surrounding the debt ceiling. Now, the mere size of the issuance is likely to increase these costs, despite the agreement on the debt ceiling.

However, not everyone believes that the issuance will cause market volatility.

Marko Papic, chief strategist at the Clocktower Group, stated, “Any unique, complex, arcane monetary-policy plumbing problem is resolved relatively quickly.”