Even if I did not work in advertising, I would still be a commercials expert. You are likely one as well. Consider all the tropes you’ve consumed over the years, such as forest-green hatchbacks overcoming rugged Western landscapes and major pizza franchises stretching miles of mozzarella. These images indicate the type of presentation you’re observing, so you won’t be baffled when the brand appears.

The same is true of a recent music video: it begins, as expected, at a barbecue where a Smash Mouth song is playing and people are laughing and drinking beer. Around three seconds in, however, your amygdala begins to call for reinforcement. The partygoers are chuckling excessively loudly. A woman appears to be conversing with her beer, which she carries in a fleshy, misshapen koozie. There are odd images of lips and drinks that cavort without ever connecting. The beverages keep growing larger, obscenely big. A fire begins to spread, engulfing the frame like the launch of a space shuttle.

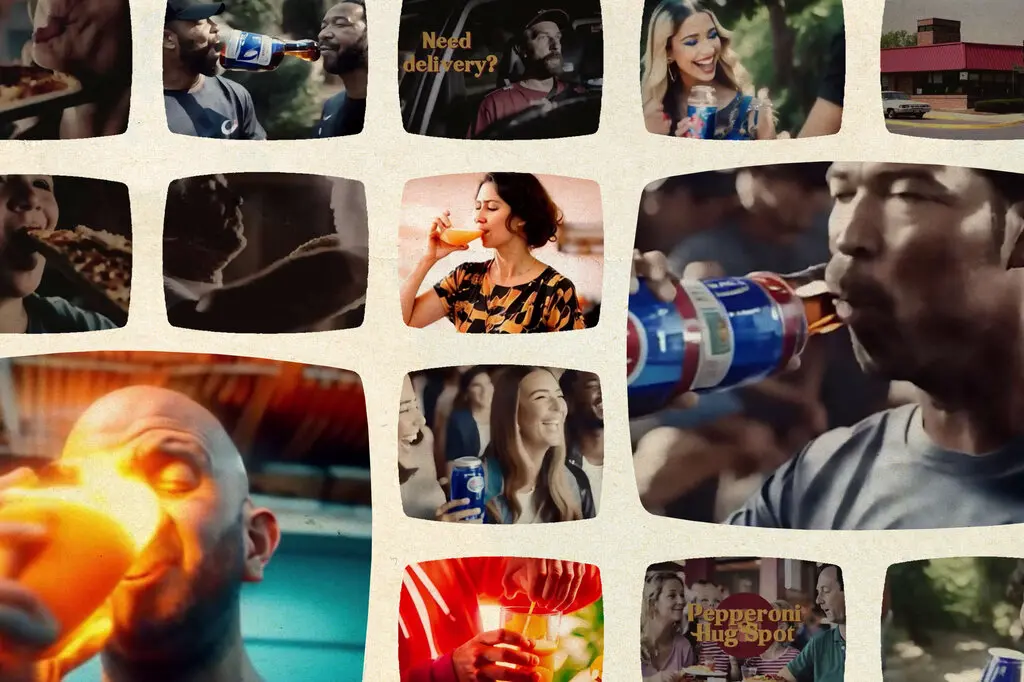

This is “Synthetic Summer,” a fictitious beer advertisement wholly generated by generative artificial intelligence. It is one of several A.I. advertisements that have been circulating online. “Synthetic Summer” is reminiscent of an Instagram post from the Cenobites in “Hellraiser”: a banquet of ungodly desires, ruthlessly satisfied. In another A.I. advertisement, “Pepperoni Hug Spot,” a family pizza restaurant is plagued by predatory mouths and erase transitions from the 1970s. Another video, a parody advertisement for orange juice by the artist Crypto Tea, features Donald Trump narrating between precise pour shots and deranged breakfasters.

The artificial intelligence is not automatically producing this bizarre content. Behind each advertisement is a mischievous tech enthusiast with an aptitude for these new tools, who nudges the situation towards absurdity. Chris Boyle, the creator of “Synthetic Summer,” informed me that his instructions for the text-to-video artificial intelligence programme included requests for more fire as the commercial progressed. In the end, however, a computer interprets these instructions: This is as near to the uncanny as you can get without using drugs or sleeping.

Considering all the various visions you could conjure with this power, it is telling that people continue to use the formulas of old-school television commercials. There must be tens of thousands of commercials available on the Internet, an enormous corpus for software to process. This accessibility has enabled our juvenile A.I. programmes to reproduce them with remarkable accuracy. In addition, commercials are recursive by design. Regardless of how much they doodle in the margins, they adhere to tried-and-true principles: sparkling suburban kitchens; slow-motion ice-and-soda splashes; pleasurable, wordless canoe excursions indicating relief from irritable bowel syndrome or moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Every convenient shorthand and overused motif is repeatedly inscribed in the advertisements themselves. AI consumes everything and sends it back in our faces.

In fact, A.I. tools such as Midjourney and Gen-2 are so devoted to commercials that the word itself commands their respect. When the director of “Pepperoni Hug Spot” added “TV commercial” to text prompts such as “a happy family eating pizza in a restaurant,” the A.I. rendered clips with more even lighting. Boyle told me that the greatest results were obtained by instructing the programme to produce “as generic and middle-of-the-road Americana as possible.”

At this juncture, commercials are America’s cave paintings: a series of symbols handed down from one target market to the next. Their visual syntax is frequently clearer to us than the supposedly-inspirational realities. My entire life has been spent training my own organic neural network on glamorised images of beachside bonfires, generic office escapades, rise-and-grind sports montages, chemically horned-up retirees, and unblemished trainers on rugged streets. Even though I have never dined al fresco to live jazz or surprised a spouse with his-and-hers new vehicles for the holidays, my mind can easily construct such moments. Now, even computers can.

Some individuals who create commercials today are concerned that A.I. could take their employment once it learns how hands function. The task of creating phoney advertisements, however, is one at which AI already excels: assistant ethnographer, media-studies expert, and impartial auditor of cultural motifs. This software, having consumed the same commercial broth as the rest of us, takes a prompt such as “family breakfast” or “outdoor party” and, based on the vast number of examples on which it has been trained, calculates a probabilistic mean. It provides a composite image of formulas and cliches, including those that we are typically too immersed in to notice.

In that orange-juice advertisement, for instance, we see two views of a classic juice pitcher, a completely unnecessary prop whose sole purpose is to distract us from the fact that the product is not freshly strained. Typically, a few citrus segments drifting elegantly inside aid in selling this illusion. The A.I. has observed this fruit but is unable to determine why it is present; as a result, the version it generates is an aberrant foreign body, a cancerous green mass that begins to consume the liquid in its entirety. In “Synthetic Summer,” the partygoers hold cans a few inches away from their faces or clasp their lips to the sides. That’s likely due to the fact that their real-life counterparts rarely consume in commercials as well; it’s a convention of alcohol advertisements to depict fun without showing anyone drinking. This visual euphemism creates a void that A.I. struggles to fill and ultimately does so with humorous and disquieting imagery. This is one of the reasons why repeated viewing of A.I. advertisements is rewarding: once you get past their grotesqueries, you begin to notice compelling signals concealed in the noise.

Until the cacophony ceases to exist. By the time these tools have compiled a genre’s clichés, the genre may have progressed. “Synthetic Summer,” for example, has the genetic makeup of a 20-year-old Bud Light commercial; it has little in common with the brand’s most recent Super Bowl advertisement. These are currently delirious visions of the recent past.

As far as marketers are concerned, this is acceptable: They do not need to train AI on advertisements from the heyday of linear television. In a fragmented and polarised world, such a consensus may be obsolete. Companies are increasingly likely to feed their A.I. reactors with every available piece of data about potential customers, including everything you’ve liked, purchased, or posted, as well as every consumer demographic you could plausibly fall into. The images and videos you see may or may not be real, but they are likely to feature the people and settings that will appeal to you the most or play on your insecurities most intimately. Which, upon reflection, could be considerably creepier than a few extra digits.