Last year, the world’s central banks underestimated inflation. They are attempting to avoid repeating the same error.

Central bankers in affluent nations are drastically raising inflation projections, factoring in additional interest rate hikes, and advising investors that interest rates will remain elevated for some time. Some have abandoned plans to maintain current interest rates.

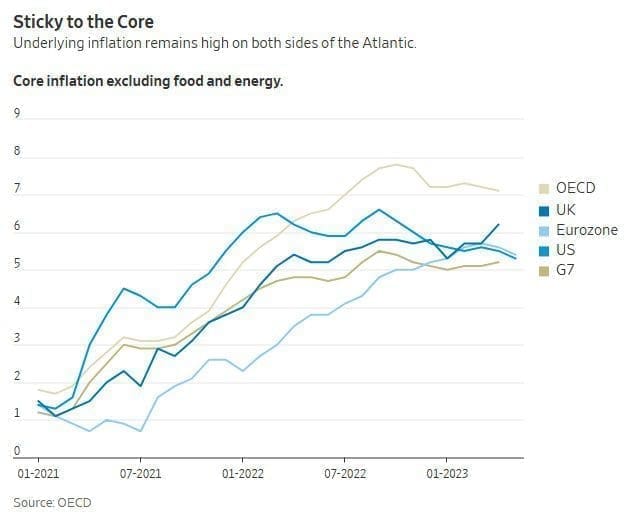

A little over a year into their campaign against elevated inflation, policymakers have yet to declare victory. In the U.S. and Europe, fundamental inflation remains at or above 5% despite the fading visibility of last year’s dramatic increases in energy and food prices. The rate of wage growth has stabilized at high levels on both sides of the Atlantic, and there are few indications of a sustained decline.

Indeed, there are indications that the impact of last year’s aggressive interest rate increases is waning, with housing markets stabilizing and unemployment resuming its decline. The eurozone has entered a technical recession, but the bloc added nearly one million new jobs in the first three months of the year, whereas the U.S. economy has lately added approximately 300,000 jobs per month. Canada, Sweden, Japan, and the United Kingdom avoided recessions after growth rebounded unexpectedly. Business surveys indicate an optimistic outlook.

All of this places major central banks in a difficult position. They must determine if inflation has halted well above their 2% target, which could necessitate much higher interest rates, or if its decline has merely been delayed.

If they make the incorrect decision, they could force the developed world into a deep recession or years of high inflation.

“Central banks are not in an enviable position,” said Stefan Gerlach, former deputy governor of Ireland’s central bank. You could make a grave error in either case.

The difficulty is exacerbated by the fact that central banks initially failed to anticipate the rise in inflation, he said. These so-called policy errors may cause officials to second-guess their decisions, as both sides of the inflation debate argue over why economists have been so off-base regarding inflation.

The Federal Reserve held interest rates constant last week but signaled two more increases this year, which would bring U.S. rates to their highest level in 22 years. In its semiannual monetary policy report released last week, the Federal Reserve stated that price inflation for core services excluding housing, a closely monitored indicator of underlying price pressures, “remains elevated and shows no signs of abating.”

Recently, the central banks of Australia and Canada startled investors by increasing interest rates, the latter after a month-long pause. The European Central Bank raised interest rates by a quarter point last week and signaled that it would continue to do so at least through the summer. Christine Lagarde, president of the ECB, stated, “We have no intention of pausing.”

Since the beginning of the year, the Bank of England has indicated a willingness to suspend its long series of interest rate hikes, but it is now expected to raise its key interest rate for a thirteenth consecutive time this week as wage and consumer-price growth remain stubborn. Investors anticipate five additional rate hikes, which would bring the bank’s main rate to 5.75 percent.

Fed Governor Christopher Waller stated on Friday in Oslo during a moderated discussion, “We’ve still been climbing, the ECB is still climbing, everyone is still climbing, and the U.S. economy is still humming along for the most part.”

British legislators have reached the end of their tolerance. Tuesday, the congressional committee responsible for examining the central bank called for an independent review of its inflation forecasts to determine what went awry.

With conflicting economic signals, central banks are entering a new phase in which they must allow sufficient time for past rate increases to permeate the economy without underestimating inflation.

There are valid reasons to hold off. During the pandemic, households and businesses may have accumulated savings that could have supported expenditure and mitigated the impact of rising borrowing costs. Businesses are extremely profitable, allowing them to retain employees despite the challenging economy. As savings are depleted, there will be a decline in expenditure, and inflation may resume its decline.

Additionally, interest rate increases may just be beginning to take effect. Businesses and households may not respond to an increase in borrowing costs from zero to one percent, but they may reduce expenditure when rates reach five percent. “It may be highly nonlinear,” Gerlach said.

Importantly, economies continue to recuperate from the pandemic. The delayed reopening of China’s economy supported global growth, which could be bolstered by new stimulus measures.

According to Holger Schmieding, Berenberg Bank’s chief economist, many close-contact services, such as restaurants and retail, still have space to recover from their precipitous decline during the period of lockdowns and social distancing. The output of consumer-facing services in the United Kingdom is 8.7% below its pre-pandemic level, whereas the output of all other sectors is 1.7% higher.

Increased expenditure on consumer-facing services will temporarily mitigate the impact of rising interest rates. However, these effects will be short-lived if economic growth continues to decelerate, which will reduce incomes and expenditure.

Friday, Francois Villeroy de Galhau, the governor of the Bank of France and a member of the ECB’s rate-setting committee, said, “The key issue now is the transmission of our past monetary decisions, which are strongly reflected in financial conditions, but whose economic effects may take up to two years to be fully felt.”

Other factors, however, imply that inflation may remain persistent.

Some Fed officials believe that interest rates are having a greater impact on the economy than in the past, suggesting that previous rate hikes may have already been absorbed by the system and that further increases are required.

Why could this be? Waller argued on Friday that central bankers now state clearly what they are doing and what they intend to do in the future, allowing investors to react promptly. Even as recently as the 1990s, the Fed did not inform investors of its most recent policy decisions during rate-hiking cycles. Before the Fed increased rates in March 2022, the yield on two-year U.S. Treasury notes had increased by 200 basis points, according to Waller.

In addition, new central bank policies may mitigate the impact of interest rate hikes. In a recent paper, Bundesbank economists argued that as interest rates increase, banks earn more on their large stockpile of excess reserves deposited with central banks, which reflects central banks’ massive asset-purchase programs. This enables institutions to continue lending.

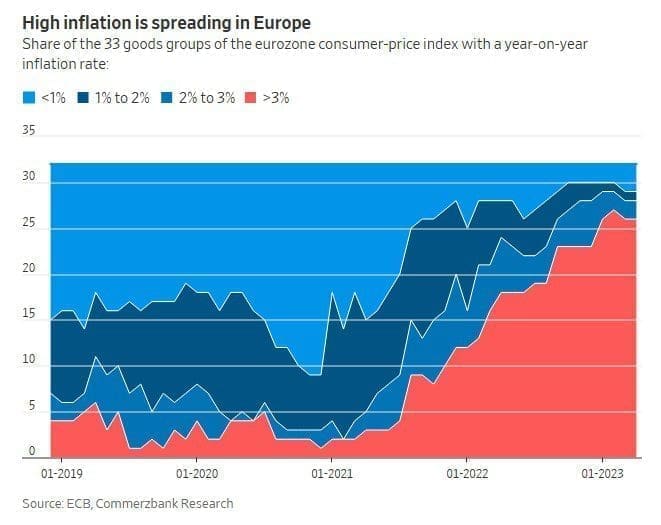

Importantly, businesses and households may have irrevocably adjusted their behavior to the new world of soaring prices. If this is the case, Joerg Kraemer, chief economist at Commerzbank in Frankfurt, stated that a return to the old world of low and stable inflation could be very costly, necessitating much higher interest rates.

Households and enterprises must respond with vigor or face severe erosions in purchasing power. Businesses can readily justify price increases if their competitors are doing the same. In addition to recruiting new members, labor unions are battling to compensate workers in ways not seen for decades.

Kraemer stated that as a result of these alterations, central banks will need to act more forcefully, driving economies into a deeper recession in order to break the new inflationary mindset. He stated that the ECB may need to increase its policy rate to 5% from its present level of 3.5%.

Currently, it appears that investors are skeptical of the hawkish tone emanating from central banks. The stock markets on both sides of the Atlantic are resilient, and investors anticipate interest-rate decreases in the United States and Europe in the coming year. According to some economists, that could be an error.

“The bottom line is that inflation at 5% is still too high, and it is evident that the markets are underestimating the Fed’s commitment to return inflation to 2%,” said Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management.