Cormac McCarthy, the enigmatic and esteemed author known for his stark portrayal of violence and outsiders in works such as “All the Pretty Horses,” “The Road,” and “No Country for Old Men,” passed away on Tuesday at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was 89 years old. His son, John, confirmed the death, according to a statement from McCarthy’s publisher, Knopf.

McCarthy’s fiction often painted a grim picture of the human condition, exploring themes of violence, isolation, and the darker aspects of human behavior. His characters were outsiders, much like McCarthy himself, who lived a quiet life outside the literary mainstream. He seldom granted interviews, never taught writing, and refrained from participating in readings or providing blurbs for other writers’ books.

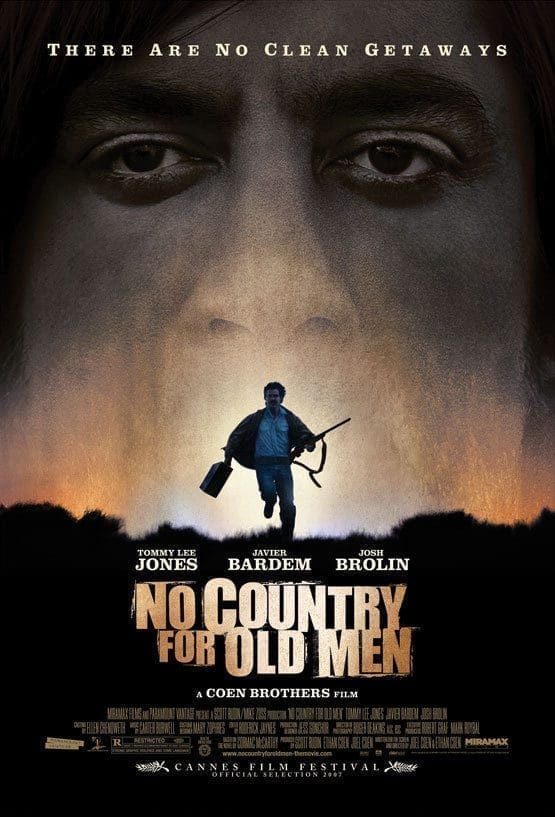

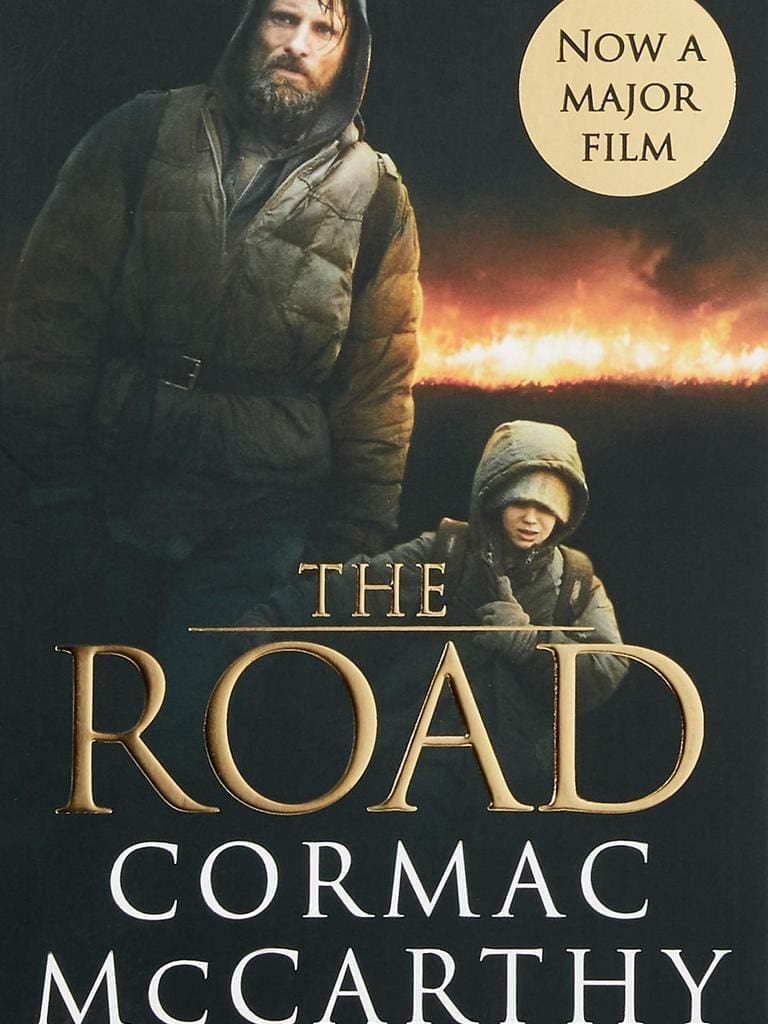

Despite his reclusiveness, mainstream success found McCarthy. His reflective western “All the Pretty Horses” won a National Book Award in 1992, and his post-apocalyptic masterpiece “The Road” earned a Pulitzer Prize in 2007. Both novels were adapted into films, as was “No Country for Old Men,” which won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 2008. The film, directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, featured a chilling performance by Javier Bardem as the nihilistic hitman Anton Chigurh.

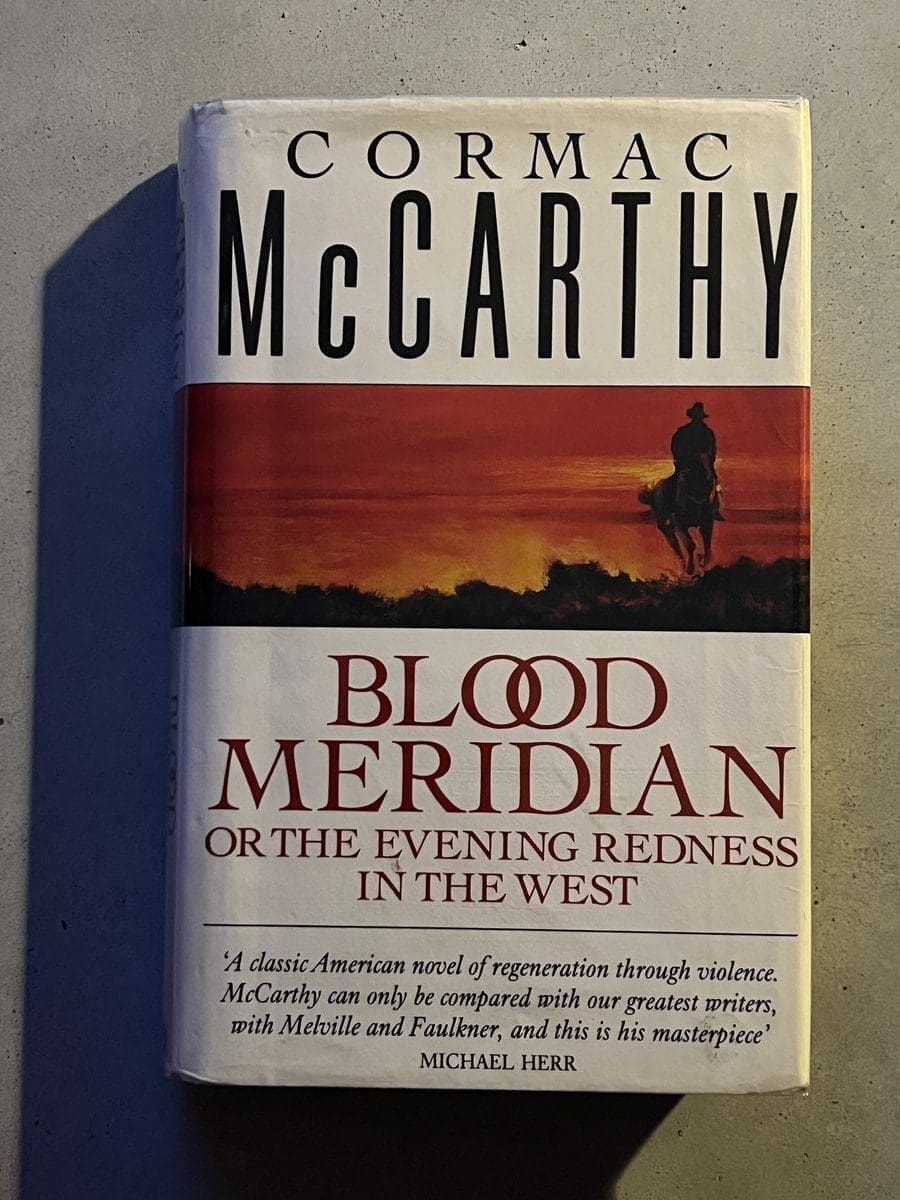

In recent years, McCarthy had been discussed as a potential Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. Esteemed critic Harold Bloom placed him among the four major American novelists of his time, alongside Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, and Thomas Pynchon. Bloom also praised McCarthy’s brutal western “Blood Meridian” (1985) as “the greatest single book since Faulkner’s ‘As I Lay Dying.'”

Notable author Saul Bellow commended McCarthy’s “absolutely overpowering use of language” and his “life-giving and death-dealing sentences.” However, accolades for McCarthy’s work were not unanimous. Some critics found his novels overly portentous and excessively masculine, with few notable female characters.

Writing for The New Yorker in 2005, James Wood lauded McCarthy as “a colossally gifted writer” with a flair for capturing the essence of Shakespearean tragedy, the King James Bible, and the works of Melville, Conrad, and Faulkner. However, Wood also critiqued McCarthy’s sometimes nonsensical sentences, his apparent fascination with violence, and his perceived hostility toward intellectual consciousness.

The Evolution of Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Style

The transformation in language and tone across Cormac McCarthy’s body of work has long been a topic of discussion among academics and his ardent readers. The essential question: Which is superior – early McCarthy or late?

McCarthy’s first four novels – “The Orchard Keeper” (1965), “Outer Dark” (1968), “Child of God” (1973), and “Suttree” (1979) – are characterized by somber fables set in the Appalachian South. These early works are written in convoluted prose that draws a clear influence from William Faulkner, an association further solidified by McCarthy’s first five books being edited by Albert Erskine, who also served as Faulkner’s last editor.

Despite their dark themes, these early novels occasionally incorporated carnivalesque humor. In “Suttree,” for instance, a character boasts about engaging in carnal activities with an entire watermelon field, much to the chagrin of the farmer who sues him for bestiality. The accused later quips, “My lawyer told ’em a watermelon wasn’t no beast.”

The latter phase of McCarthy’s career commenced with “All the Pretty Horses,” the inaugural volume of his acclaimed Border Trilogy, which also features “The Crossing” (1994) and “Cities of the Plain” (1998). This period showcases McCarthy’s deep and instinctive understanding of the American landscape, as his fiction shifts to the desert Southwest. His prose, now rich but austere and nearly devoid of punctuation, bears more resemblance to Hemingway than Faulkner.

The melancholic nature of “All the Pretty Horses,” populated with existential cowboys, took some of McCarthy’s fans by surprise. Novelist Leslie Garrett, a friend of McCarthy’s, reportedly commented, “Cormac finally has succeeded in writing a book that won’t offend anybody.”

“All the Pretty Horses” garnered a substantial audience, leading to a 2000 film adaptation starring Matt Damon and Penélope Cruz. The novel marked not only McCarthy’s first bestseller, but also his first work to achieve significant sales. Prior to this, none of his books had sold more than 5,000 hardcover copies.

Early Life in Tennessee

Born Charles McCarthy on July 20, 1933, in Providence, Rhode Island, Cormac McCarthy was the third of six children and the oldest son of Charles J. and Gladys (McGrail) McCarthy. A few years later, the family relocated to Knoxville, Tennessee, where his father, a Yale Law School graduate, worked as a lawyer for the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Cormac changed his name from Charles to avoid associations with Charlie McCarthy, the ventriloquist Edgar Bergen’s dummy. Other accounts suggest he renamed himself after an Irish king or that his family legally changed his name to the Gaelic equivalent of “son of Charles.”

Raised in an affluent Knoxville home with house staff, the young McCarthy was drawn to the city’s seedier side. He attended Knoxville’s Catholic High School and later the University of Tennessee, studying physics and engineering from 1951-1952. In 1953, he joined the Air Force and served four years, several of them stationed in Alaska, where he read numerous books to quell his boredom.

Returning to the University of Tennessee from 1957-1959, McCarthy discovered a knack for language after a professor asked him to read a collection of 18th-century essays and repunctuate them for a textbook. He began publishing short stories in the student literary magazine but never graduated. He moved to Chicago, working in an auto-parts warehouse while writing his first novel.

McCarthy sent the manuscript of his debut novel, “The Orchard Keeper,” to Random House, as it was the only publisher he knew. Although Orville Prescott’s review in The New York Times praised the book as “impressive,” he also noted that McCarthy’s imitation of Faulkner’s literary devices and mannerisms partially obscured his own talents.

For many years, McCarthy wrote in relative obscurity and poverty. After his first marriage to Lee Holleman ended in divorce, he married English pop singer Anne DeLisle in 1966. The couple lived in a dairy barn outside Knoxville for nearly eight years, struggling financially. McCarthy declined speaking engagements in favor of focusing on his writing.

McCarthy’s second novel, “Outer Dark,” received praise for its language, “compounded of Appalachian phrases as plain and as functional as an ax.” His third novel, “Child of God,” was a dark tale about a cave-dwelling mass murderer and necrophiliac. Author and child psychiatrist Robert Coles called McCarthy a “novelist of religious feeling” and likened him to classical Greek dramatists.

In 1976, McCarthy moved to El Paso after separating from DeLisle. The settings of his novels soon changed as well. His last early novel set in the South, “Suttree” (1979), was his most autobiographical. Some saw the novel as a farewell to his raucous old life. McCarthy stopped drinking before the novel was published, saying, “If there is an occupational hazard to writing, it’s drinking.”

In 1981, McCarthy was living in a Knoxville motel when he learned he had won a MacArthur fellowship. His journey from a rebellious youth in Tennessee to a renowned author had begun, and his literary career was poised to flourish.

A Journey Through His Literary World

Acclaimed author Cormac McCarthy, known for his vivid and unyielding prose, has crafted a literary legacy filled with tales of violence and human struggle. Among his most celebrated works is “Blood Meridian,” a surreal and blood-soaked anti-western that many critics believe to be his finest book. Set in Texas and Mexico, the novel explores the dark world of scalp hunters and outlaws, with a central character reminiscent of Melville’s Captain Ahab—a brilliant, seven-foot tall albino judge.

The MacArthur Fellowship, often referred to as the “genius grant,” awarded McCarthy the time and resources needed to write this masterpiece. He described the book’s characters as “a legion of horribles” that were “half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners.”

After the retirement of his longtime editor, Mr. Erskine, McCarthy transitioned from Random House to Alfred A. Knopf, joining forces with editor Gary Fisketjon. Fisketjon, who had also worked with renowned authors like Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, and Tobias Wolff, played an instrumental role in McCarthy’s career. It was during this time, just before the release of “All the Pretty Horses” in 1992, that McCarthy agreed to his first major interview with The Times Magazine.

Richard B. Woodward, the article’s author, observed that the reclusive McCarthy lived a simple life, cutting his own hair and eating meals from a hot plate or in cafeterias. In the interview, McCarthy expressed his admiration for writers like Melville, Dostoyevsky, and Faulkner, while dismissing others like Proust and Henry James as “strange.”

“All the Pretty Horses,” a gritty yet romantic tale about a young man named John Grady Cole, quickly became a bestseller, selling nearly 200,000 copies within six months. Although the next two books in the Border Trilogy also enjoyed commercial success, some critics were not as enamored with them.

McCarthy spent many years working at the Santa Fe Institute, a nonprofit scientific research center. He relished the company of scientists and even volunteered to help copy-edit science books, trimming them of extraneous punctuation. In a 2007 Rolling Stone profile, McCarthy expressed his fascination with physics, questioning why anyone wouldn’t be interested in such a field.

In 2005, McCarthy published the existential thriller “No Country For Old Men,” which was followed by “The Road,” a harrowing novel about a father and son’s struggle to survive in a post-apocalyptic world. Dedicated to his son, John, McCarthy revealed in a Rolling Stone interview that his thoughts about the world’s future often centered on his child.

An enigmatic figure in the literary world, McCarthy has never voted in an election, claiming that “poets shouldn’t vote.” As he continues to capture readers’ imaginations with his unyielding prose and unforgettable stories, his profound impact on modern literature remains undeniable.

A Look Back on the Life and Work of McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy, the celebrated author, sold his archives to Texas State University in 2008 for $2 million. The collection, consisting of 98 boxes filled with letters, drafts, notes, and unpublished works, provides a glimpse into the author’s life and creative process. In an unexpected twist, McCarthy’s iconic Olivetti typewriter, which he used to write each of his novels, sold at auction in 2009 for $254,500. The author immediately replaced it with an identical model, costing less than $20.

In 2012, McCarthy ventured into the realm of screenwriting with “The Counselor,” a story about a Southwest lawyer entangled in the drug business. The screenplay was adapted into a film by Ridley Scott in 2013, featuring Michael Fassbender and Cameron Diaz among its star-studded cast.

McCarthy’s personal life saw its share of ups and downs as well. He married Jennifer Winkley, his third wife, in 1998 when he was 64 and she was 32. The couple divorced in 2006. McCarthy is survived by two sons, John and Chase, from his third and first marriages respectively; two sisters, Barbara Ann McCooe and Maryellen Jaques; a brother, Dennis; and two grandchildren. His first wife, Ms. Holleman, passed away in 2009.

In late 2022, McCarthy published two ambitious and interconnected novels, “The Passenger” and “Stella Maris,” receiving widespread praise from critics. “The Passenger” follows the story of Bobby Western, a racecar driver turned salvage diver, whose life parallels McCarthy’s in several ways. The novel delves into themes such as mathematics, the nature of knowledge, and the importance of fast cars.

“Stella Maris,” the second novel, centers around Alicia Western, a 20-year-old doctoral candidate in mathematics at the University of Chicago. Alicia, who is also Bobby’s sister, checks herself into a psychiatric hospital in Black River Falls, Wisconsin, due to hallucinations. Their father had been a physicist on the Manhattan Project.

Before McCarthy’s passing, it was revealed that he had been working on a screenplay for a film adaptation of “Blood Meridian.” The project is set to be directed by John Hillcoat, who previously directed the film adaptation of McCarthy’s “The Road.”

In a rare media appearance, McCarthy participated in a 2007 interview with Oprah Winfrey on her daytime television show. Winfrey had chosen “The Road” for her book club, but McCarthy appeared uneasy in the limelight. Reflecting on the experience, he told Winfrey, “You spend a lot of time thinking about how to write a book, you probably shouldn’t be talking about it. You probably should be doing it.”